Stephanie Brito

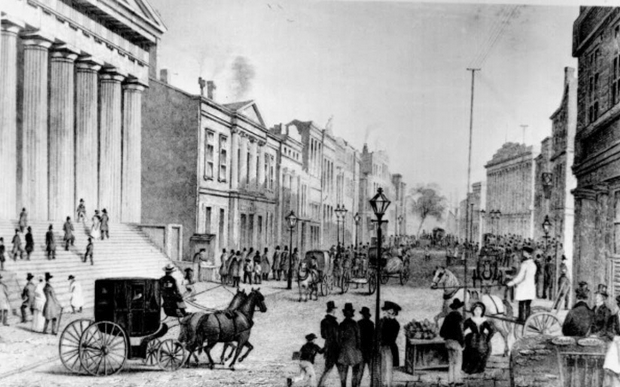

As students in New York City, one may think it is hard to find parallels between our lives and British literature. However, there is history here in the city where we see the impact of the transatlantic slave trade. The area that we now know as Wall Street was built by slaves transported by British ships. Wall Street was essentially where enslavers would auction off slaves. Slaves built “the wall” where on the other side they built their own communities.

After reading Oroonoko: The Royal Slave by Aphra Behn, we learned of the tragic tale of Oroonoko. Behn’s travel narrative lets the reader witness Oroonoko’s enslavement and shipment to a new land. Although Behn could have written this “true history” with a different approach, I wanted to think about how I could use this text as an educator here living in New York City. I have the privilege of working with NYC students from grades 6-11 as a tutor. I help students mainly with literacy, and after reading Behn’s story I thought this would be a good text to bring up to one student I was tutoring. I had the student read a few excerpts, and asked this student how he could relate to Oroonoko. The conversation we had, and the paper I asked him to write was one of the best moments I’ve had as a tutor.

My student made connections to his life as an Afro-Latino in a predominantly white school, and thought that he and Oroonoko both were at a disadvantage. I asked him, “Why?” and he simply replied, “because we’re black.” He argued that Oroonoko was royalty, but he still ended up dead. He then asked, “So what happens to me?” I understood what my student was trying to argue. I made the counter argument that Behn had written a story about a black man, and was one of the most successful and well known books that Behn had written. Although Behn is a white woman, and it took a white author to gain sympathy over the atrocities that took place. I wanted my student to understand that Oroonoko’s story was something that needed to be told. I realize that what my student was trying to argue was that as a black male he has more hurdles to overcome in comparison to someone who is privileged, but it’s those hurdles and how we face them define who we are. We may live in one of the most diverse cities in America, but discrimination and hate is still unfortunately present in our society.

I decided to take my student on a small trip to Lower Manhattan so we could both learn more about the history in our city. We went to the African Burial Ground National Monument. The memorial paid tribute to the 15,000 Africans that were buried there from 1690s to 1794. When we arrived my student expressed to me that he felt profound sadness, but at the same time he felt proud of his ancestry and how they were not forgotten. I was glad that we took the trip down to the memorial to learn more about the connections between Oroonoko and our beloved city.

Work Cited:

Behn, Aphra. Oroonoko. 1688.

Amma

As an immigrant to the United States, from a young age, being part of the minority was significant to the world I grew up in. The language barrier hit me the most, followed closely by physical appearance. Being from Ecuador, I was small, tan skin, with dark eyes and hair. Nothing like the dominant group that was your typical light hair, light eyes, light skin individuals. The Americans. I did not have a status with power, I was with no rights. I was never personally subjected to discrimination or ill treatment because of who I was, but regardless the feeling of inferiority was all around. If I place myself in the picture, which I have failed to do, and look at Equiano’s experience, it becomes easier to embrace and understand his individual idea of freedom as a form of survival.

In the text, The Interesting Narrative of Olaudah Equiano by Olaudah Equiano himself, one element that I failed to understand, but continued to judge, was the tone of Equiano towards the English. As I read his work, I couldn’t help but shake my head over and over again as Equiano made his enslavement out to be like an adventure. If his work would have been used to introduce me, a non-American, to the history of slavery, then I would have thought that slavery was not as bad as history made it out to be. As if the tone of the story was not misleading enough, I was flabbergasted when even within his African culture slavery was present. Of course he makes the distinction that such slaves are criminals or prisoners of war, but was Equiano not a prisoner to the English? The difference is the treatment of course, but both were prisoner and both had to surrender their individual freedom. They both answered to a figure of authority. To me, that was ironic.

Equiano remarks, “Those prisoners which were not sold or redeemed we kept as slaves: but how different was their condition from that of the slaves in the West Indies! With us they do no more work than other members of the community, even their masters…Some of these slaves have even slaves under them as their own property, and for their own use” (Ch. 1). Here, he definitely, emphasizes on how differently he treats slaves in comparison to slavery done by the participants in the West Indies slave trade. In his home, slavery is good, perhaps even a kind act towards prisoners. The English had many tropes in regards to Africans, some in which they saw them as uncivilized cannibals. I couldn’t help but think if the English thought they were being “kind” when taking Africans away from such primitive world and introducing them to the wonders of the modern. Reading Equiano’s voyage as an enslaved person, that is exactly what he expressed. As if the wonders of the modern world make up for enslavement as a whole just because he found it fascinating.

While he almost brags about how his culture treats “slaves,” he rebukes other forms of slavery. He says, “Such a tendency has the slave-trade to debauch men’s minds, and harden them to every feeling of humanity…it is the fatality of this mistaken avarice, that it corrupts the milk of human kindness and turns it into gall…Surely this traffic cannot be good, which spreads like a pestilence, and taints what it touches! which violates that first natural right of mankind, equality and independency… For it raises the owner to a state as far above man as it depresses the slave below it” (Ch. 5). Here, slavery is definitely presented as bad and immoral. In my eyes both are forms of slavery, one more severe than the other, but both nonetheless deprive absolute freedom. In the West Indies, there might have been cases were the enslaver might not have been as brutal to the enslaved, perhaps they showed kindness, but still the enslaved remained enslaved, no matter the treatment there was no equality, no freedom.

Equiano was definitely kind towards the English in his text. And while I did judge him for it, especially because once freed he participate in a society that upheld slave trade, as an immigrant I somewhat understand it. As someone who came from the outside, he was exposed to the emergence of race, the awareness of blackness, of modern clashing with premodern, among other things. When confronting these things my instinctive response is to fit it, to assimilate, which is what he perhaps did when he started dressing like the English, and reading and writing, embracing Christianity, or even working. Except his tools to assimilate happened to depend on the slave trade. Above all, his assimilation was for a grand purpose, and that was to write this abolitionist “slave” narrative. Equiano’s idea of freedom, short-term, was that of individual freedom. But only by gaining his individual freedom, could he become a sort of ambassador for ending enslavement, and thus for the long run, pursue or encourage the collective idea of freedom.

Work Cited:

Equiano, Olaudah. The Interesting Narrative and Other Writings. 1789.