|

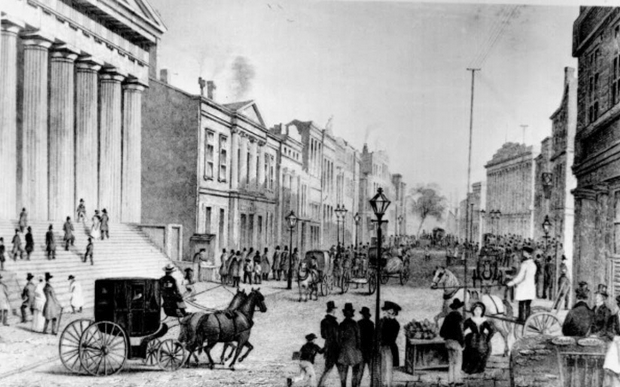

Stephanie Brito As students in New York City, one may think it is hard to find parallels between our lives and British literature. However, there is history here in the city where we see the impact of the transatlantic slave trade. The area that we now know as Wall Street was built by slaves transported by British ships. Wall Street was essentially where enslavers would auction off slaves. Slaves built “the wall” where on the other side they built their own communities.

After reading Oroonoko: The Royal Slave by Aphra Behn, we learned of the tragic tale of Oroonoko. Behn’s travel narrative lets the reader witness Oroonoko’s enslavement and shipment to a new land. Although Behn could have written this “true history” with a different approach, I wanted to think about how I could use this text as an educator here living in New York City. I have the privilege of working with NYC students from grades 6-11 as a tutor. I help students mainly with literacy, and after reading Behn’s story I thought this would be a good text to bring up to one student I was tutoring. I had the student read a few excerpts, and asked this student how he could relate to Oroonoko. The conversation we had, and the paper I asked him to write was one of the best moments I’ve had as a tutor. My student made connections to his life as an Afro-Latino in a predominantly white school, and thought that he and Oroonoko both were at a disadvantage. I asked him, “Why?” and he simply replied, “because we’re black.” He argued that Oroonoko was royalty, but he still ended up dead. He then asked, “So what happens to me?” I understood what my student was trying to argue. I made the counter argument that Behn had written a story about a black man, and was one of the most successful and well known books that Behn had written. Although Behn is a white woman, and it took a white author to gain sympathy over the atrocities that took place. I wanted my student to understand that Oroonoko’s story was something that needed to be told. I realize that what my student was trying to argue was that as a black male he has more hurdles to overcome in comparison to someone who is privileged, but it’s those hurdles and how we face them define who we are. We may live in one of the most diverse cities in America, but discrimination and hate is still unfortunately present in our society. I decided to take my student on a small trip to Lower Manhattan so we could both learn more about the history in our city. We went to the African Burial Ground National Monument. The memorial paid tribute to the 15,000 Africans that were buried there from 1690s to 1794. When we arrived my student expressed to me that he felt profound sadness, but at the same time he felt proud of his ancestry and how they were not forgotten. I was glad that we took the trip down to the memorial to learn more about the connections between Oroonoko and our beloved city.

Work Cited: Behn, Aphra. Oroonoko. 1688. |

|

Antwan Weatherington As an African-American male living in American who is in between two generations, I feel that I can see the themes and ideas concerning 18th century British colonialism from a rather interesting vantage point. As a person in my late 30’s, I grew up as a teenager in the 1990s when the country was going through many battles concerning racism. Many of the scars left behind from slavery and the aftermath of Reconstruction were being ripped open. In the 1990s, there seemed to be a reemergence of black pride but with the aggression of a newer generation expressing it through music, fashion, and politics. I can remember having my older relatives around me who lived in this country when being the “right kind of black” was a matter of life or death. In these times it was either fall in line, keep your head down, or risk you and your family’s safety. Listening to my elders, I know they dealt with racism which morphed into colorism within my community: Some family members were more socially accepted by their own because they were lighter skin, or their hair was of a finer texture than their counterparts. These standards were not created by African-Americans but were pasted down to them through colonialism. It was someone coming in and saying who you are, what you are, and what you believe is not correct. We were systematically fed this message for so many generations that well after slavery we took on those standards as our own. Hearing the way in which Behn describes Oroonoko in compared to other Africans infuriated me. She was indoctrinating to her readers that a certain kind of black person is more beautiful and acceptable. Aphra Behn doesn’t seem to think it at all possible that all these features could be coming only from his African heritage when she says, “His nose was rising and Roman, instead of African and flat” (Behn 6). This truly illustrated the contradiction with some abolitionists of that time. Yes, they didn’t want Africans to be slaves but by no means were they considered beautiful without some European enhancement. It also illuminates my own bias, ignorance, and pre-programming when it comes to another African Americans features I see in passing. If they do not look like what I think a black person should look like, in my mind, they must be “mixed.”Although this was fiction, it became reality for the African American community and the United States in modern times. This is something that I see time and time again in media: African-American men and women being told by their own race and others what is and is not beautiful. A prime example of this is an incident that happened between two female castmates of a VH1 show called Basketball Wives, in which a women of Latin descent with far more European features compared a Nigerian young lady with prominent African features to a monkey over social media. It was eye opening to see the response from African-American women who didn’t think she was beautiful either and used other cruel names for her physical attributes. Although I am not a native New Yorker I can feel the reverberations of colonialism in society today repackaged as gentrification. The term gentrification has many connotations depending on whom you ask and which side of the profit margin you own. I see it as an influx of residents of higher socioeconomic status moving into a low socioeconomic status neighborhood. When I originally moved to New York back in 2000 I lived in East Flatbush, Brooklyn. This area is known for its diverse mix of West Indian, African, Jewish, and African-American populations. Over the last 10 years this neighborhood like many others around the country has been transformed into an almost unrecognizable, socially acceptable, even “hip” place to live at the expense of long term residents. In thinking back to Oroonoko’s story told through the eyes of Behn,where she obviously had preconceived notions about people who she knew nothing about, by saying “He had nothing of barbarity in his nature” (Behn 5). Her feeling was something I could relate to, ashamedly, evening being a person of color. The only things I knew about Africa was what I saw in movies and through National Geographic. I thought there was only huts and dirt and no one who spoke English. The lawmakers, real estate developers are allowed to come into an area and people either have to assimilate into a new way of life or move out. The people aren’t even considered for the value and knowledge they bring to a place they have lived for generations. The men in Oroonoko were described as people who knew they did not know the land and needed the native people as a means for survival. What also happens are the small businesses that have been the vein of that community must fall in line with the new ways of the neighborhood or be forced out as well. Although this process makes the neighborhood pretty on the outside it causes more of a rift and makes the line between classes that much bigger. This problem is illustrated in “Uniting the Kingdom” (2007) when it says, “Internal colonialism did little to alleviate the gap between the poor and the rich, instead exploiting that divide (Levine 24). The readings in this class have made me open to the experience of validating points of views and ideals that I might not agree with but are an integral part of society that must be unpacked and rediscovered.

Works Cited: Behn, Aphra. Oroonoko. 1688. Levine, Phillipa. “Uniting the Kingdom.” The British Empire: Sunrise to Sunset. Pearson, 2007. |

|

Amma As an immigrant to the United States, from a young age, being part of the minority was significant to the world I grew up in. The language barrier hit me the most, followed closely by physical appearance. Being from Ecuador, I was small, tan skin, with dark eyes and hair. Nothing like the dominant group that was your typical light hair, light eyes, light skin individuals. The Americans. I did not have a status with power, I was with no rights. I was never personally subjected to discrimination or ill treatment because of who I was, but regardless the feeling of inferiority was all around. If I place myself in the picture, which I have failed to do, and look at Equiano’s experience, it becomes easier to embrace and understand his individual idea of freedom as a form of survival. In the text, The Interesting Narrative of Olaudah Equiano by Olaudah Equiano himself, one element that I failed to understand, but continued to judge, was the tone of Equiano towards the English. As I read his work, I couldn’t help but shake my head over and over again as Equiano made his enslavement out to be like an adventure. If his work would have been used to introduce me, a non-American, to the history of slavery, then I would have thought that slavery was not as bad as history made it out to be. As if the tone of the story was not misleading enough, I was flabbergasted when even within his African culture slavery was present. Of course he makes the distinction that such slaves are criminals or prisoners of war, but was Equiano not a prisoner to the English? The difference is the treatment of course, but both were prisoner and both had to surrender their individual freedom. They both answered to a figure of authority. To me, that was ironic. Equiano remarks, “Those prisoners which were not sold or redeemed we kept as slaves: but how different was their condition from that of the slaves in the West Indies! With us they do no more work than other members of the community, even their masters…Some of these slaves have even slaves under them as their own property, and for their own use” (Ch. 1). Here, he definitely, emphasizes on how differently he treats slaves in comparison to slavery done by the participants in the West Indies slave trade. In his home, slavery is good, perhaps even a kind act towards prisoners. The English had many tropes in regards to Africans, some in which they saw them as uncivilized cannibals. I couldn’t help but think if the English thought they were being “kind” when taking Africans away from such primitive world and introducing them to the wonders of the modern. Reading Equiano’s voyage as an enslaved person, that is exactly what he expressed. As if the wonders of the modern world make up for enslavement as a whole just because he found it fascinating. While he almost brags about how his culture treats “slaves,” he rebukes other forms of slavery. He says, “Such a tendency has the slave-trade to debauch men’s minds, and harden them to every feeling of humanity…it is the fatality of this mistaken avarice, that it corrupts the milk of human kindness and turns it into gall…Surely this traffic cannot be good, which spreads like a pestilence, and taints what it touches! which violates that first natural right of mankind, equality and independency… For it raises the owner to a state as far above man as it depresses the slave below it” (Ch. 5). Here, slavery is definitely presented as bad and immoral. In my eyes both are forms of slavery, one more severe than the other, but both nonetheless deprive absolute freedom. In the West Indies, there might have been cases were the enslaver might not have been as brutal to the enslaved, perhaps they showed kindness, but still the enslaved remained enslaved, no matter the treatment there was no equality, no freedom. Equiano was definitely kind towards the English in his text. And while I did judge him for it, especially because once freed he participate in a society that upheld slave trade, as an immigrant I somewhat understand it. As someone who came from the outside, he was exposed to the emergence of race, the awareness of blackness, of modern clashing with premodern, among other things. When confronting these things my instinctive response is to fit it, to assimilate, which is what he perhaps did when he started dressing like the English, and reading and writing, embracing Christianity, or even working. Except his tools to assimilate happened to depend on the slave trade. Above all, his assimilation was for a grand purpose, and that was to write this abolitionist “slave” narrative. Equiano’s idea of freedom, short-term, was that of individual freedom. But only by gaining his individual freedom, could he become a sort of ambassador for ending enslavement, and thus for the long run, pursue or encourage the collective idea of freedom. Work Cited: Equiano, Olaudah. The Interesting Narrative and Other Writings. 1789. |

|

Jessica Umana I’ve been living in New York my whole life but I actually moved to New York City about two years ago. I am completely disappointed in the world and how society has become. Living in the city has really been an eye opener for me. Not because I don’t like it, but because it seems as if everyone is living their own rushed life and doesn’t care about anyone but themselves. There’s not much of any appreciation towards nature and its beauty anymore. Instead, people live their lives working and thinking about themselves. In the poem, “The World is Too Much with Us” by William Wordsworth, the speaker is angry at the world and its lack of appreciation towards nature. He accuses the modern age for losing connection with nature and forgetting its meaning. I completely agree with Wordsworth and that is why this poem impacted me the most. I strongly believe that everyone is so focused on their own life that they tend to forget the real meaning of the world. He says, “ Little we see in Nature that is ours; / We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!” In this quote, the reader is able to feel the speaker’s tone and it is evident that he is angry at what the world has become. He is disappointed on how it has given away its heart to the things that don’t matter, such as technology. Furthermore, I was able to connect with this poem because everyday, I see how the world disconnects more and more from its natural environment. It’s upsetting to see that happen. Now that we are in quarantine, it has given us the opportunity to love nature around us more and appreciate the things we don’t normally appreciate when we are free. However, I don’t think that a pandemic like the one we are currently living in should have to take place for people to change their selfish actions. Moreover, the speaker says something very essential. He states, “The world…getting and spending.” Once again, I thought of NYC when I read this line of the poem. They call it the “city that never sleeps.” That is because everyone is so focused on getting money and working all the time. Everyone is always rushing to get to work and become something in this world. It reminds me of a competition. Overall, I do believe that there was a greater appreciation towards nature in the past. Back then, technology wasn’t as advanced as it is today and that is one of the reasons why people had to use the environment around them in order to make useful resources to survive. Now that technology has taken over the world, people are relying on it to the point that they can’t live without it and it should be the other way around. Nature should be appreciated more in order to make the world a better place. Work Cited Wordsworth, William. “The World is Too Much with Us.” 1802. |

|

Isela Larreinaga When diving into the course of English 302, several topics and ideas come to mind. It can get quite overwhelming if time is not taken to analyze the works being read and to formulate our own thoughts and opinions. This course introduces us to the idea of slavery, freedom, colonization, trauma, and so much more. Each piece of literary work presents their own perspective of how history was made and the everlasting consequences that come from it. It’s crucial to understand the significance of each story told and how it plays a role in the way history is taught to others. In Olaudah Equiano’s autobiography The Interesting Narrative and Other Writings, we’re presented with the horrors of slavery and the never-ending desire for freedom. Equiano doesn’t fail to paint vivid images of his experiences and the near-death experiences that will forever haunt him as he roams the Earth. It’s important to note that Equiano made it clear that not every person, especially those who were white, were barbaric. He described many relationships he formed in a positive light, he grew close to many and often felt terrible being sold to a different person. Yet even with the positive memories of certain people and places, he doesn’t neglect the idea that many others like him didn’t have the luxury. Most were often beaten to death and disregarded, abused, and taken advantaged for the slightest things. Equiano mentions the “Many times [he have] seen these unfortunate wretches beaten for asking for their pay; and often severely flogged by their owners if they did not bring them their daily or weekly money exactly to the time’” (101). The need for freedom was at an all time high; many risked their lives to escape or ended up committing suicide because it was better than being on Earth. Slavery took a toll not only on the physical aspect but emotionally and mentally. Equiano painted freedom to be unrealistic at one point because buying your freedom didn’t truly hold its weight. He contradicts himself when he believes freedom is the only way to overcome the horrors of mistreatment but even as a freed man he’s chased down to be beaten and viewed as inhumane. This narrative helps to present both perspectives of history without disregarding one another; most textbooks tend to paint a story in a one linear point-of-view, not giving other perspectives the ability to present themselves and to be heard. Slavery is a very complex and misunderstrood topic yet Equiano single-handly shows the complexity of it and what it truly means to be enslaved and the cost of freedom. With the novel of Oroonoko by Aphra Behn, we’re told a story from the perspective of a white woman, which already raises questions. In Oroonoko, the prince is seen as handsome – like no other black man seen before. He is praised for his physical attributes but is quickly dismissed when he’s forced to become a slave in the colony of Surinam. The perspective that we imagine is a very romanticized way of viewing the history of slavery and humanity. Throughout the novel, Behn presents a positive attitude towards enslavement because it helps to strengthen England and other major powers. In short, Behn didn’t disagree with colonization, allowing the story of Oroonoko to be quite biased. Yet her outtake on these topics helps readers to form their own thoughts even if her ideas and opinions don’t resonate with people. Behn makes it quite clear she’s not a reliable source due to her several contradictions of Oroonoko. She loses herself in appreciating his physical looks which is altered to satisfy the acceptable standards that England and Western countries had intact. When Oroonoko attempts to fight for his freedom, Behn now describes him as shameful and a threat to the colonizers. He is drawn out to be barbaric and deceitful, and in return, he was to be killed off in a cruel manner because he brought it onto himself. Before his death, he was beaten and tortured, during which Behn says: “if before we thought him so beautiful a sight, he was now so altered that his face was like a death’s head blacked over, nothing but teeth and eye-holes” (75). In his last moments, he is dehumanized and is just a name that once lived. This novel helps readers to understand the different thought processes and how one’s action is justified (even if it’s morally wrong). There’s also the many poems written by Phyllis Wheatley, the first African-American to become a published author of a poetry book. Wheatley contributes to the subject of slavery in a different light, she often expresses appreciative toward those who bought her from Africa. In her poem, “A Farewell to America, to Mrs. S.W.,” Wheatley describes her journey to England and the potential effect her departure will have on Susanne Wheatley. With this poem being directed towards Susanne, readers can grasp the idea that not every enslaved person suffered harsh nights. Yet, Wheatley doesn’t fail to expose the hidden truth and agendas of certain people. Just like Equiano, she didn’t fail to mention the horrible conditions and lives others were living in and made it known that it was wrong. She often used religion within her poems and recognized the fact that in the eyes of God, slavery and discrimination wasn’t morally right. God wouldn’t turn anyone away and many colonizers and enslavers grew blind to that perspective. This course is quite complicated if you look at it from a broad point-of-view. There’s many stories that haven’t been told because they were silenced but we can’t neglect the stories we do have. Each experience contributes to the development of history and how we recognize certain moments. The novels, select poems and short-stories provided an insight into a topics widely spoken about but not as in depth as we would like. Works Cited Behn, Aphra. Oroonoko. 1688. Equiano, Olaudah. The Interesting Narrative and Other Writings. 1789. Wheatley, Phyllis. “A Farewell to America. To Mrs. S.W.” 1773. |